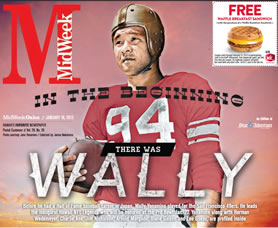

In The Beginning There Was Wally

Meanwhile, he joined a local all-star team that scheduled a tour of West Coast universities. He starred in the first game, at Portland’s Multnomah Stadium, impressing a 49ers scout who was actually there to watch Hawaii-born Portland quarterback Charles Kawainui Liu. Three games in California followed, and the number of scouts showing up to watch Wally grew with each. In the spring of 1947, he accepted the offer from Ohio State. Preparing to leave, though, he was invited by 49ers coach Buck Shaw to come to San Francisco for a tryout. Shaw was impressed, and offered a two-year, $14,000 contract. That was big money in 1947, and his parents were still laboring at Olowalu. Deciding, “I ought to help the folks,” he became a 49er.

cover_9

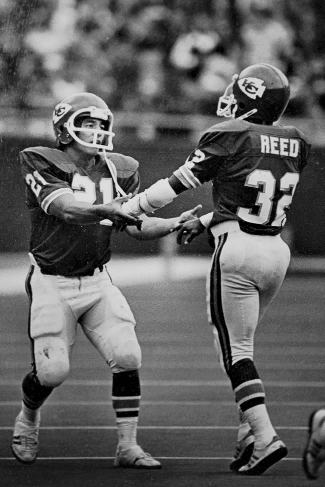

Arnold Morgado

Most of us can't understand Arnold Morgado's feelings about the NFL. Not because he played in the league for four years, with all the Inside the Huddle shows and a 24/7 network dedicated to the sport, fans know more about the league than ever. Rather, we can't understand why he isn't as rabid about the NFL as the rest of America.

"I am not a fan, it was work for me for so long, so I am too critical," says Morgado, who has spent the past 14 years working as a financial adviser for Merrill Lynch.

This is not to say he doesn't love the game. You can't work as hard as he did making it to The League and not have a fire for the sport. He just doesn't spend his Sundays on the couch yelling at the TV. When you earn something, it means more than just a cheap thrill on weekends.

His climb was a steep one from the start.

Growing up on an Ewa plantation, he was not the typical Punahou student. He worked in the cafeteria to help finance his education, and performed well enough on the field to get into Michigan State, where he spent a year before returning home to run the ball for the 'Bows and butt heads with Coach Dick Tomey over efforts to recruit local players.

"I don't know if I worked harder than anyone else - work was just part of my everyday living," says Morgado. "It is how you become successful. You are not waiting around for someone to give it to you, but you work hard to do it yourself."

The same held true in the pros. He went undrafted out of college and beat the streets until he found a job hauling the rock for the Kansas City Chiefs.

"I would have gone anywhere, but Kansas City was where I could be afforded an opportunity," says Morgado, who spent from 1977 through '81 there while amassing 15 rushing TDs and just under a 1,000 yards for his career.

He spent some time away from the game, but returned this year to his alma mater to help coach the running backs in hopes that the lessons he learned fighting his way to the top filter down to the next generation.

"I like commitment and effort as a coach and a player," says Morgado. "Those are really learned qualities and I hope it spills over into their personal lives."

-C.P.

As Robert Fitts writes: “Wally would never have to work on the plantations again.”

But his football days were numbered.

Returning home after his first promising season in San Francisco, Wally went to work for a trucking company, thinking the lifting and carrying would strengthen him. He also played AJA baseball for the Athletics (later to become Asahi). He fractured a thumb sliding into a base in an exhibition game at Hilo, and reported to the 49ers with a cast on his hand. With him unable to play, and with the 49ers having just signed another speedy running back – future Hall of Famer Joe “The Jet” Perry – the team voided the second year of Wally’s contract, costing him $7,000.

Fitts reports Wally was “disappointed, really sad. Football was the sport I really loved. In the off-season, I just fooled around with baseball.”

Not ready to give up football, he signed with the Hawaiian Warriors of the Pacific Coast Pro Football League for the 1948 season. While Wally again starred on the field, the league was failing at the box office, and it folded before season’s end.

He was invited to the 49ers training camp in 1949, but despite flashes of brilliance was cut. Back in Hawaii, he again joined the Warriors, who were embarking on an East Coast barnstorming tour. Playing against the Patterson (N.J.) Panthers, Wally intercepted a pass and during the runback was crushed from behind by a much larger player, badly dislocating his left (throwing) shoulder. His days of throwing a football 70 yards on the fly were done.

And with that, Wally’s football career was finished too. He turned to baseball, with a huge helping hand from former big-leaguer Lefty O’Doul. His ties to Japanese baseball went back to 1931 when he was part of a touring Major League all-star team, and like so many gaijin fell in love with the country and its people. Following the war, he returned to Japan several times to help reinvigorate the game, including managing the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League during an exhibition tour in 1949. Passing through Honolulu on the way home, he heard about a promising young player. Thus Wally was invited to join O’Doul’s Seals for spring training. “Wally has a perfect swing,” O’Doul told reporters, “and he’s strong.”

He wound up in Salt Lake City, where he starred, and after the ’50 season O’Doul helped arrange for Wally to sign with the Yomiuri Giants in Tokyo.

He joined the Giants for the 1951 season, and succeeded from the start, reminiscent of his debut football games for Lahainaluna and Farrington.

In his first at-bat for the Giants, he bunted for a hit. On the ensuing play, sliding with spikes up to break up a double play, he knocked the shortstop down. This was shocking to fans and players, because the norm for Japanese runners was to veer into right field, politely conceding the out at second base. And when Wally drew a bases-on-balls, he ran to first base, just as he sprinted to his position in the outfield – foreign practices for Japanese players then.

He’s been called the Jackie Robinson of Japanese baseball, and with good reason, though as Wally said later, “the difference is that I was the same color they were, and I couldn’t speak the language.” Wally was initially loathed for his aggressive American-style play. He was cursed because he was American, and as a nisei had not returned to the Motherland to fight – worse, he’d served in the U.S. Army and was “the enemy” for many fans and several teammates who’d served in the Imperial military during the war. Taking his place in centerfield, rocks were thrown and landed at his feet, but he never responded, Robinson-like in his determined calm. Teammates often ignored him. But he persevered, leading the Giants to the Japan title, homering in the clinching game. For the season, he hit .354, stole 26 bases in 30 attempts, and scored 47 runs in 54 games.

That would open the door for other Hawaii boys to play in Japan, including his friends Jyun Hirota and Dick Kitamura, and more than a thousand Americans have since played in Japan. Yonamine would play 12 seasons in Japan with a career .311 batting average, retire as a beloved hero, earn a place in the Japan Hall of Fame as both player and manager, and be honored by the Emperor with the Order of the Sacred Treasure, the first professional athlete to be so cited.

And he did it in an aggressive style he first learned on the football fields of Hawaii.

He also did it in a quiet, local-boy style that seems to have created the model for the humble heroics of Oregon’s Marcus Mariota and Notre Dame’s Manti Te’o this season, among many other Isle athletes at colleges large and small, and in the NFL.

“I’m just a boy from Olowalu,” Wally told Fitts. “I’ve never forgotten my roots and where I started … People tell me I’m a living legend and a big star, but inside I don’t feel I’m any different from anybody else. I’m just one of the guys – the same person I was growing up. I’ve been fortunate, and I’m just happy I can give something back to Hawaii and help others fulfill their dreams.”

Did he ever.

Wally Yonamaine died Feb. 28, 2011, after a long battle with prostate cancer.

For more on Wally Yonamine and his wife Jane, see Page 12 or click here