A Punchbowl Memorial For Ernie Pyle

My Uncle Bud landed in France soon after DDay, June 6, 1944. He fought across Europe, came home and went about his life.

He never talked about it. He’d seen many things he didn’t want to remember, even for a nephew eager to hear war stories from America’s last good war.

Growing up in the 1950s, I embraced that war. I played “war” with other kids on the block and discovered a book on the bottom shelf of a relative’s bookcase: Here Is Your War, a collection of war correspondent Ernie Pyle’s columns from the North African and European fronts during World War II.

It told the story of America’s everyman on the front lines of a good war, the story my uncle and countless other veterans preferred not to tell.

By war’s end, Pyle’s columns were appearing in more than 700 newspapers across the country. They were read by parents, spouses, lovers, children — all who worried about those whose letters always ended with “Don’t worry about me.”

They worried. Sixteen million Americans served in the military during World War II, 70 percent of them overseas. From the North Africa and Italian campaigns to the Normandy invasion and the Pacific theater, Ernie Pyle wrote his columns, letters home, if you will, to all those loved ones.

Pyle was born to it. He knew the loneliness of an only child and he grew up shy. At Indiana University he found his shield against shyness: a reporter’s notebook. He majored in journalism and worked on the Indiana Daily Student.

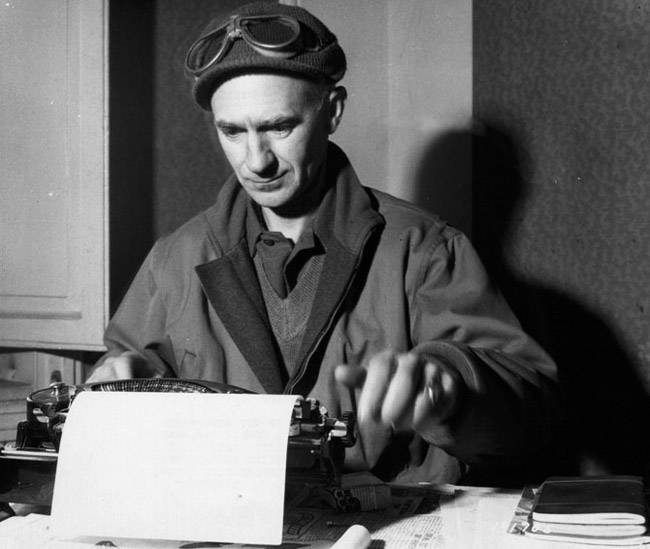

He left college in his senior year to join the journalist’s trade, eventually becoming a roving correspondent and columnist for the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain in 1935. During the next five years, he drove across the United States 35 times, wearing out three cars and an equal number of typewriters. His columns from the road made him famous.

Pyle made it to Hawaii. “He wrote simple, gripping pieces about five days spent with the lepers at Molokai,” according to his obituary in The New York Times, “and put his feelings on paper: ‘I felt unrighteous at being whole and clean,’ he told his readers.”

In 1940, the war in Europe came and Pyle wrote from London. After the United States entered the war, Pyle followed the “GIs.” In May of 1943, from Tunisia he wrote: “I love the infantry because they are the underdogs. They are the mud-rain-frost-and-wind boys. They have no comforts, and they even learn to live without necessities. And in the end they are the guys that wars can’t be won without.”

He described a passing line of infantrymen: “For four days and nights they have fought hard, eaten little, washed none, and slept hardly at all. Their nights have been violent with attack, fright, butchery, and their days sleepless and miserable with the crash of artillery.

“They don’t slouch. It is the terrible deliberation of each step that spells out their appalling tiredness. Their faces are black and unshaven. They are young men, but the grime and whiskers and exhaustion make them look middle-aged.”

That quality of prose won Pyle a Pulitzer Prize in 1944. On April 18, 1945, still following the infantry, Pyle was killed by enemy fire on the island of Lejima off the coast of Okinawa.

On Saturday (April 18), the Ernie Pyle 70th anniversary memorial celebration will take place at National Cemetery of the Pacific at Punchbowl. It begins at 9:45 a.m.

dbboylan70@gmail.com