A Low-vision Breakthrough

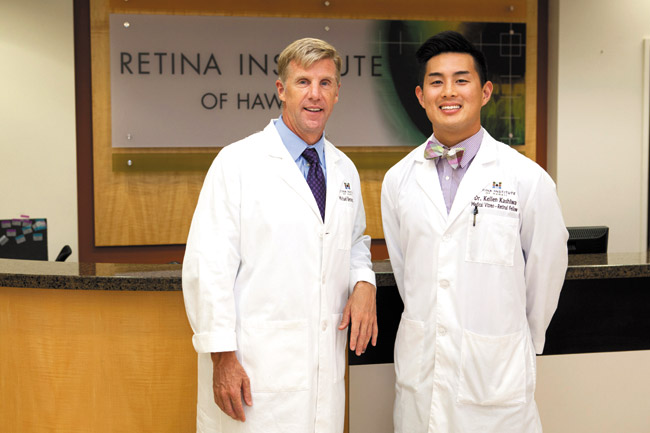

Drs. Michael Bennett And Kellen Kashiwa

Ophthalmologists at Retina Institute of Hawaii

What is your role at Retina Institute of Hawaii?

Dr. Bennett: I founded Retina Institute in 2001 and I have been in practice for more than 20 years.

mw-dih-dr-michael-bennett-and-dr-kellen-kashiwa-ac-01

Dr. Kashiwa: I received my optometry degree from Pacific University College of Optometry in Oregon and began training with Dr. Bennett at Retina Institute in 2008. I am a low-vision specialist, so I’m excited about the new technology called Argus II. For patients who lose the ability to see their loved ones, who lose the ability to do the things they love, I come in and find tools — low-vision devices like the new Argus II — to help improve their quality of life and help them see their loved ones.

Bennett: We are ophthalmologists who subspecialize in retina. Ophthalmology involves correcting all of the diseases that affect vision. Retina is the neuroscience or brain surgery aspect of that. We take for granted what we see every day: colors, people, vision, depth. The retina is this little thing in the back of your eye that’s the size of a postage stamp, as thin as a piece of tissue paper, that’s responsible for sending all that information to your brain. You mess that up and the whole world can change. Or, if you can fix that, you can open up a new world.

What is the Argus II?

Bennett: It’s a two-part system. It’s a device that opens up worlds to people who are blind. There is an external camera that’s hooked up to a battery pack that you can fine-tune to send visual signals to an electrical chip that we implant inside the eye. A blind patient fitted with the Argus II can pick up large objects, big letters on the eye chart, figures moving back and forth. Signals are being sent from the camera to the retina. So now we can adjust the camera system on the outside to pick up a decent field of view out in front of us to pick up objects, letters, doorways. For somebody who sees the world in white and black, or absent blackness, this is beyond a breakthrough. It’s pretty amazing.

Who is the best candidate for this? Is it for people born blind or those who once had vision but lost it?

Bennett: We’ve all seen an apple, so our brain can register what an apple is. People who have had formed vision previously, their brain knows exactly what that is because they’ve seen it. Argus II is approved for retinitis pigmentosa, a disease in which the sensing cells of the eye that are responsible for picking up that apple, or object ― those cells, those photoreceptors no longer work. But the rest of the visual system is completely intact. So this new electrode or computer device, this bionic eye that we can put inside the eye, will pick up that object through the external camera, and send that object to that electrical chip. That electrical chip stimulates the optic nerve, and now they can see.

It’s a two-part system. There’s the external camera with a battery pack and Wi-Fi sensor, and then that will send the information when it’s picked up to the retinal chip. The retinal chip is what stimulates the optic nerve in the whole brain pathways. Those patients who have had vision, this is their chance to regain some portion of that once again.

The patient can see motion and black-and-white gradients. That is where we are currently. This rendition is black and white, but maybe ultimately we can get to something down the line that has greater pixels and color variation.

What is retinitis pigmentosa?

Bennett: Inside the eye are photoreceptors, rods and cones that identify black-and-white and color. In retinitis pigmentosa, those photoreceptors are what die or quit working. Everything else is completely functional. The computer chip is a replacement for those light-sensing rods and cones. So the optic nerve has worked in the past, and we help it to work again, to a degree. I believe there are many more people who can benefit in future generations, but retinitis pigmentosa is what the Argus II has been designed for to date.

Is Argus II new in Hawaii?

Bennett: It’s new in the world. I’ve been involved with the inventors for decades now. As this has progressed, Kellen and I have been on board. They’ve approved a handful of centers around the world, which are all large academic centers: University of Miami, UCLA, University of Michigan, or hospitals in London. We are the first private practice and first Hawaii surgeons approved to provide this to everybody in the Pacific.

Have you started using it on patients?

Bennett: We are still waiting for the first one to arrive. The Argus II is expensive and it’s a brand new procedure. Right now we’re trying to partner with major hospitals on the island. We’re in the final fundraising stage. We need about $65,000 worth of equipment and computer tools that can get this fit for the patient. We have half a dozen patients ready to go. We’re right on that precipice.

How long will the recovery process be?

Bennett: I equate this with a broken bone. The surgery is relatively straightforward. It’s like surgeries associated with retinal surgery plus a little bit complicated, with the external device that is involved. But just like a broken bone, these people haven’t seen for a long time, so now we have to readapt the body, like a patient learning to walk again. They’re not going to just jump up the next day like nothing has happened. In rehab, some patients are doing extremely well within a month or two. Other patients improve over the entire first year.

The occupational work then goes to Kellen, as far as getting the patients to be able to fine-tune the image and learn to navigate with that image. It takes somebody like Kellen, who has ridiculous amounts of care and talent, and a patient who is motivated to get this to work.

What kind of training is involved?

Kashiwa: We take small steps to help the patients utilize their vision, utilize this new type of technology that’s going to help them see their loved ones, see the silhouette, be able to navigate through hallways and function. It takes a lot of effort, but what they put in is what they’re going to get out of it.

Is it about exercising the eye to get it to function again?

Kashiwa: It’s more of a sense of being able to interpret and utilize the information that’s getting sent back to the brain.

Bennett: It’s almost like a fuzzy television set. If we “adjust the rabbit ears” the vision, the camera, will pick up the information and send the silhouettes and big letters back to the patient. The patient has to realize, “What was that object I was just seeing? In what world am I looking at this?” — and then learn how to navigate.

I talked to a man who had retinitis pigmentosa, and he lost all of his vision. He had the Argus device that was put in during the trial period. He had always heard his grandson playing soccer on the field, and he was now able to stand on the sidelines and see the outline of his grandson playing soccer. Grandpa now got to enjoy what his family was doing. That was a tearjerker. His whole world was black. Now he has the ability to see again ― not exactly clear faces, but to pick up those kinds of enjoyable things in life.

For more information, call 955-0255 or visit retinahawaii.com.