George Takei Pledges To ‘Allegiance’

‘Only dumb actors invest in their own projects,’ says the legendary George Takei. ‘Well, I must be a dumb actor because I have a lot in Allegiance,’ a play based roughly on his family’s internment camp experience during WWII. Led by Dr. Mark Mugiishi, more than 100 Hawaii investors chipped in at least $25,000 each to produce the show that is due to open on Broadway in the fall, and which Takei says must come to Hawaii

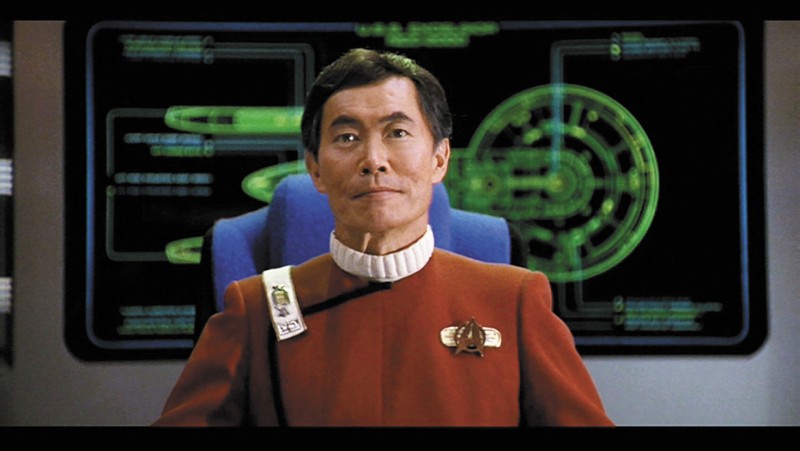

Call him resilient. Call him a political activist, a social justice champion. Or call him Sulu.

But Star Trek’s George Takei has just added a new title:

“Can you believe, I’m a debutante, at 78!” he says.

Paving the way for Asian Americans on the celluloid frontier — “I boldly went where few Asian Americans went,” laughs Takei — he became one of the most recognized Star Trek faces on TV and film, and he’s a veteran theater performer, having appeared onstage in Los Angeles, off-Broadway and throughout the UK. But as for Broadway proper, the right show has not presented itself … until now — with a musical called Allegiance. Thanks in large part to generous Hawaii donors, it will debut on Broadway beginning with a series of preview performances Oct. 6, leading up to opening night Nov. 8 at Longacre Theatre. And it’s been a long time coming, on a journey ripe with serendipity.

The story begins, fittingly, at a Broadway showing of In the Heights, a musical about a struggling Dominican-American family in New York. Takei was particularly moved by a song, Inutil, in which a father expresses feeling useless because he wants to send his daughter to college, but economic and cultural circumstances won’t allow it. The situation hit close to home for Takei.

“That father’s anguish reminded me of my father’s anguish when we were in the Rohwer Internment Camp in the swamps of Arkansas,” he says, adding with a chuckle, “I’m one of these people called criers, so tears were pouring down my face.”

Intermission arrives with the unwelcome glare of bright lights, and who happens to see Takei’s private moment of emotion but the production team of Jay Kuo and Lorenzo Thione. The three got to talking about the World War II internment of Japanese Americans, and Kuo and Thione, who had been hunting for a new project, went home transfixed by their conversation with Takei.

“Two weeks later, Jay sent me a song and there I was at my computer, crying again,” says Takei.

The song would become the first of many for a musical inspired by the WWII internment of Takei’s own family.

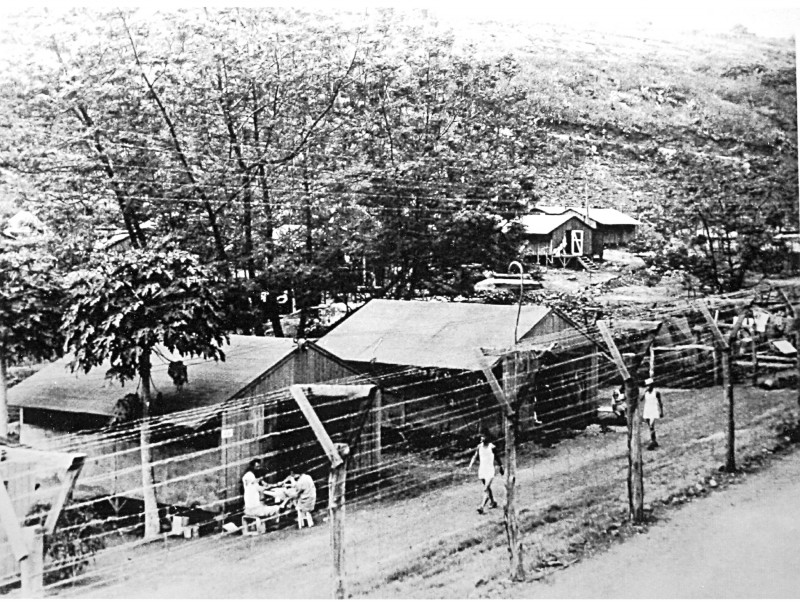

Let’s visit the dawn of the war. Takei’s Japanese-American family are well-todo Californians. He is 5 years old, his brother 4, and he has a brand-new baby sister. But then Pearl Harbor happens. Suddenly, they find themselves bereft of home and belongings, and living in repurposed horse stables before being transported to the barbed wire fences of Arkansas for four years, where life was austere, with communal bathing and waiting in line for unappetizing victuals in a noisy mess hall.

Oahu’s Honouliuli Internment Camp in 1945 PHOTO BY R.H. LODGE. COURTESY OF JAPANESE CULTURAL CENTER OF HAWAII / AR19 COLLECTION

Being released from the camp four years later was no piece of apple pie, either. Many of those who had been detained chose to resettle on the East Coast, but Takei’s family opted to return to L.A. However, housing prospects were dismal, and the family was forced to settle in skid row. Takei distinctly remembers the “ugly, scary, smelly” scene, where the acrid stench of urine was all-pervasive and the despair of the surroundings was rivaled only by its decrepit inhabitants. The little 9-, 8- and 4-year-old Takei children stood in shock one day as a disheveled man came lurching toward them and promptly collapsed and vomited on the sidewalk.

“My baby sister shrieked, ‘Mama, let’s go back home!’ Skid row was so horrible. And all she knew was the camp. Living in imprisonment had become our normality.”

Back in school in L.A., a teacher called Takei “Jap Boy.” Ever kind and positive and a fighter for civil rights, Takei has a knack for standing in the other person’s proverbial shoes. He reflects for a moment, that perhaps the teacher had a husband or son who’d been sent off to fight or even died in the Pacific battle. Yet here was a teacher, a nurturer of young minds, publicly shaming her student with a hurtful epithet.

“But that’s what we came back to,” says Takei.

Despite the bitter soil, he prospered, eventually becoming student body president and a Boy Scout. As a teen, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement sparked a new fire in Takei, and his father fanned the flame:

“I learned about our American democracy from the man who suffered most from the interment in our family. He lost our business, our home and our freedom in the middle of his life — everything that he had worked for. He said to me, ‘Our democracy is a people’s democracy, and it can be as great as the people can be, but it’s also as fallible as people are.’ My father shaped me and made me a political activist and social justice advocate.”

That abiding sense of ethics and his personal passion for musical theater intersect in Allegiance.

“Drama reaches the heart and mind, but music has the power to move people emotionally,” he points out.

We return to the moment where Takei is sitting at the computer, listening to the first song that would grow into the show Allegiance, and his cheeks are streaked with tears. In the song, the father of the fictional family is confronted with the infamous questionnaire Japanese Americans were asked to fill out. After the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese Americans flocked to recruitment centers, like other Americans, but they were peremptorily categorized as “enemy non-aliens” and imprisoned.

“A year into imprisonment, the government realized that there’s a wartime manpower shortage and here are all these people who they labeled enemy non-aliens. How to tap them for the military? They came down with a loyalty questionnaire which was a series of about 30 questions,” says Takei. “Allegiance tells the story of how the loyalty questionnaire comes down and fractures this fictional family.”

The questionnaire presented at least two controversial questions — about bearing arms and foreswearing loyalty to the Emperor of Japan — wherein the context is so murky that there’s hardly a way to answer them without compromising one’s integrity. In Allegiance, a brother and sister end up on opposite sides of the questionnaire. The brother, who is caught up in a forbidden relationship with a white woman, answers in a way suitable to government protocol. His sister is in love with a law student who has been banished to internment, and the young lawyer confronts the questionnaire in a way that doesn’t jeopardize his principles.

(from left) Lea Salonga as Kei Kimura, Telly Leung as Sammy Kimura, George Takei as Ojii-san and Paul Nakauchi as Tatsuo Kimura in the world premiere of ‘Allegiance’ in 2012 at The Old Globe in San Diego. Photo by Henry DiRocco

“For his very courageous, very American stance, he’s tried for draft evasion, found guilty and thrown into federal penitentiary. That’s the setup of the drama. It’s powerful, it’s moving. It’s a story of how the resilience of the people can rise above the stupidity of the government.”

In addition to George Takei himself, starring in the musical are Telly Leung and Lea Salonga (both Broadway stars in their own right) — all regular Hawaii visitors.

Takei recalls the day he auditioned Salonga in his living room, and their mutual admiration:

“To hear her singing in our house, that crystalline voice just soaring through the house was a real thrill. We discovered later, she was sitting in the living room tweeting, ‘Oh, wow, I’m in Sulu’s living room.’ She was as excited about being in our home as we were to have her in our home and hear her sing.”

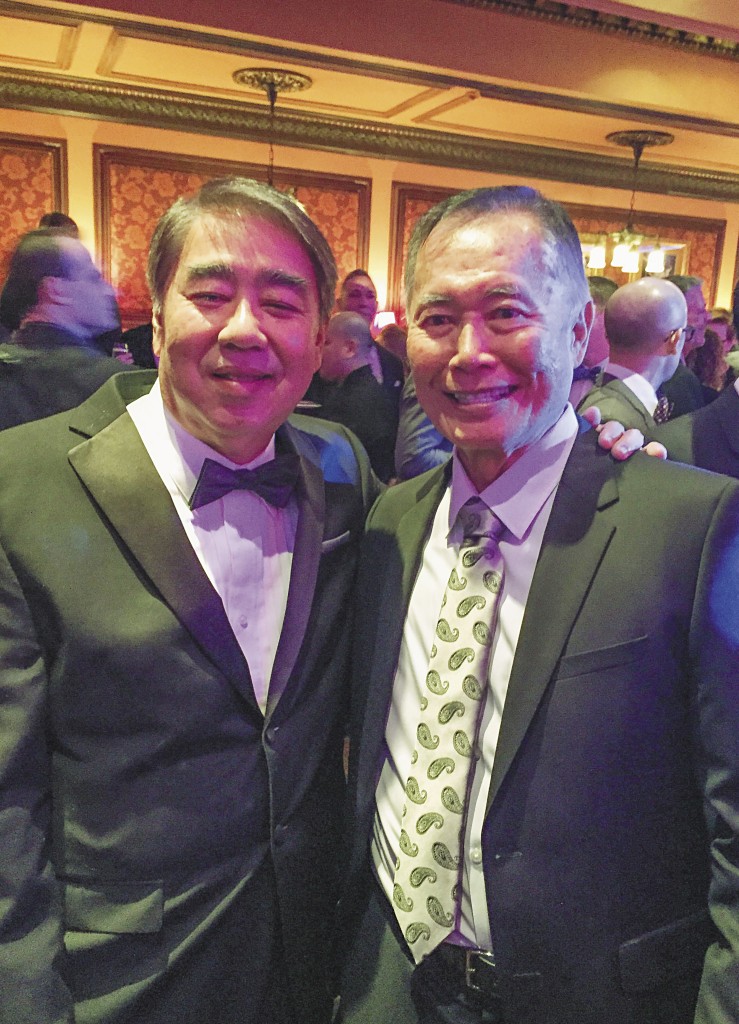

Meanwhile, on Takei’s last visit to Hawaii, he and husband Brad met local fashionista Anne Namba, and got a lot of attention for their new Namba tuxes in Los Angeles — at a gala where Takei was the guest of honor — benefiting the Japanese American National Museum (which Takei helped found and which will benefit from Allegiance ticket sales).

When they’re not admiring Hawaii’s haute couture, Takei and Brad love sampling Island cuisine, especially at La Mer.

“We like to eat early so we can see the ocean and then see the sun go down as we dine, and the way they light up the beach right there by Halekulani, and listening to the (live) music coming from the lawn.”

There’s a long road a show must travel to make it to Broadway, and it’s taken Allegiance a good several years and $13 million to get there. A show needs to prove audience interest and staying power before being accepted in the big league, and a conventional way to do that is to have a pre-run in another city. Allegiance had its very successful three-month run in 2012 at The Old Globe in San Diego.

Hawaii’s Mark Mugiishi (former Iolani basketball coach, current surgeon for Central Medical Clinic and Kuakini Hospital, and medical director at HMSA, among other hats) helped band together more than 100 investors to give Allegiance its needed push.

“Without breaking confidences and telling you what percentage came from Hawaii, I can tell you that the minimum investment a person could make was $25,000. It’s substantive,” says Mugiishi.

Mugiishi was on board from day one, having met Jay Kuo (another frequent Hawaii visitor) sometime earlier through a mutual Iolani alum. When Kuo shared his vision, Mugiishi was instantly taken with the project.

“Being a third-generation Japanese American who grew up in Hawaii, I’m familiar with Japanese-American history and Hawaii’s unique role during World War II,” says Mugiishi. “Part of the reason we’ve had so much success getting Allegiance to resonate with Hawaii people is not only is it a brilliant piece of art — the show has fantastic music and a great story, it has all of the elements that make a musical succeed on Broadway — but it also has specific and important ties to Hawaii’s history. It’s really something Hawaii can be proud of that this will be on Broadway. And the context and message are important for the rest of the United States to learn about.”

While the subject matter is solemn, Allegiance is ultimately uplifting.

“There are marriages, births, redemptions after people fall out and then reconcile,” says Mugiishi. “It’s a portrayal of life, but during a time where the villain of the day was intolerance and bigotry.”

As a personal friend of Takei’s, Mugiishi confirms that the man with the delectable bass voice is every bit as giving of himself as portrayed by his social media image:

“We ran for three months at The Old Globe, and people would come to watch George, basically. Knowing he would have a show to do the next night, he would still stand outside and shake everyone’s hand and chat with whoever wanted to meet with him. He did that every night that the show ran.”

Takei is so invested in the show that he has personally helped finance it. Says Takei, “A Broadway musical is a risky throw of the dice, and you really have to believe in the project. (It’s said that) only dumb actors invest in their own projects. Well, I must be a dumb actor because I’ve got a lot in Allegiance. But because of that and because I consider Allegiance to be my legacy project, I deeply appreciate the tremendous support that has come from Hawaii. My good friend, Dr. Mark Mugiishi, has been a real champion.”

For Hawaii folks ready for some big city excitement, Takei conjures a tantalizing vision: “Fall is a wonderful time for a vacation in New York. The temperature is just right. Central Park is turning golden and orange and blazing. It’s a beautiful time to come.”

Allegiance will run as long as seats are filling up, and Broadway shows that do well often go on the road.

“One of the first logical places to take Allegiance on tour would be Hawaii,” notes Mugiishi.

“Absolutely, coming to Hawaii is a must,” agrees Takei. “I mean, the 442nd is there, it’s their story.”

Hawaii, and Pearl Harbor in particular, do stand at the forefront of the World War II stage. We have our own intimate history with internment camps and the young Asian-American battle heroes who emerged during that egregious episode in American history. With Allegiance, Takei gives a human face to the suffering and perseverance that marked a spirited generation of mistreated Americans — one that would benefit the world to learn more about.

To get tickets, give support or learn more about Allegiance, visit allegiancemusical.com.