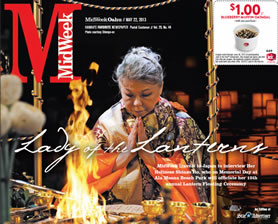

Lady of the Lanterns

MidWeek travels to Japan to interview Her Holiness Shinso Ito, who on Memorial Day at Ala Moana Beach Park will officiate her 15th annual Lantern Floating Ceremony

TACHIKAWA, Japan – About to conduct her 15th annual Honolulu Lantern Floating Ceremony on Memorial Day at Ala Moana Beach Park, her image has become so familiar on local newspaper front pages and TV screens (broadcast live since 2007), you might assume she resides in Hawaii. She does not, though she does have a temple here.

cover_1

Preparing to interview her at the home temple of Shin-nyo-en, the Buddhist lineage her father founded and she now leads, when I mentioned the upcoming trip to friends and associates, everyone seemed to know of her, but almost nothing about her or her faith: Oh, yeah, that floating lantern lady.

As it turns out, almost a year to the day after I shook hands and questioned the Dalai Lama in Honolulu, I was in this western Tokyo suburb to interview Her Holiness Shinso Ito. She is the rare Japanese woman to attain Buddhist “master” status – enlightenment as well as academic accomplishment.

She is a big deal in Japan. Daigo-ji temple in Kyoto, founded in the year 874 and today a Japanese National Treasure and U.N. World Heritage Site, invited her to officiate a ceremony on the anniversary of the founder’s death in the main temple – such an out-of-the-ordinary event it made headlines across Japan. So remarkable, it’s been called “epochal.”

“That they allowed me to do that, they must have surprised the rest of Japanese Buddhist society,” Her Holiness says with a soft laugh.

In a world filled with religious tumult and divide, hers is a voice of calm, reason, inclusion and peace. She always invites religious leaders of other faiths to participate in the Lantern Floating Ceremony at Ala Moana.

It is not about religion, she says. “It is about people.”

Last year she was invited to Kenya, where she officiated a fire ceremony with tribes that traditionally have been at odds, and often at war. Like the Achala Buddha that is revered in Shin-nyo-en Buddhism – he holds a sword in one hand to cut away destructive behaviors and attachments – the Kenyan warriors used implements of war, spears and arrows, in a peaceful ceremony. The peace remains.

She also has conducted a service at St. Peter’s Cathedral in New York City, a block from Ground Zero, and once officiated a service with Jewish, Christian and Muslim clerics. On Sept. 21, she will conduct the first Lantern Floating at New York’s Central Park.

And last month Her Holiness became the first woman priest to officiate a Mahayana Buddhist ceremony at Wat Paknam, a revered Theravada Buddhist temple in Thailand, bringing the two paths together in peace.

This is her story, and the story of how Lantern Floating came to Hawaii.

“I think it is a very beautiful thing that we can have a sense of gratitude for the past and pass it along to the future.”

She was born as members of her father’s up-start temple – located in the front of her parents’ small, traditional wood frame home – were in the midst of chanting prayers. Her mother Tomoji, having already borne four children, knew well what those quickening contractions meant and silently slipped out of the temple proper into a small side room.

There, on tatami mats, the girl who would one day make Lantern Floating a beloved Memorial Day tradition in Hawaii entered the world and was given the name Masako. It was April 25, 1942.

“In those days, they were having services in the morning, afternoon and evening,” the woman now known as Her Holiness Shinso Ito says through interpreter Yoshie Takasugi at Shinnyo-en’s modern home temple complex a short walk from the original temple. (It’s clear from her response to my questions that she understands English, but is more comfortable speaking in her native language.)

“And it was during chanting for the evening services that I was born – that is the story my mother told me. So though I don’t remember, I was born during the chanting, and that was the first thing I heard.”

It was a far less auspicious occasion then than it may seem today when Shinnyoen, which she has led since 1989, claims nearly 1 million members at 101 temples in Japan, and 19 temples and 19 training centers in more than 15 countries – including a temple at Beretania and Isenberg streets in Honolulu’s Moiliili neighborhood. The local congregation was founded in 1971 (see page 44).

“I have five siblings – two elder sisters, two elder brothers and one younger sister,” she says. “We lost those boys at young ages, 2 and 15, but even after that I had two elder sisters, so I was thinking I would be supporting them (in their religious pursuits), and I enjoyed that role. I was not the kind of person to say, ‘I will be taking care of this.'”

Young Masako’s early life goals were not so different from her current work trying to alleviate human suffering.

“When I was going to elementary school, I was fascinated with the story of the nurse Florence Nightingale, how she was so caring to people,” she says. “And then later, Madame Curie, the scientist, I wasn’t sure if I was smart enough to achieve what she did, but I was very interested.

“In high school, I was still interested in science, and my teachers thought I would make a good doctor, and I was very happy about that idea too. But gradually I started thinking I need to support my elder sisters in spiritual matters.”

That was not to be, but her path to leadership of Shinnyo-en was not the straight-line sure thing you might imagine.

Her earliest and most basic Buddhist teaching came from her mother Tomoji, in what followers today refer to as “kitchen sermons” – neighbors and friends often came to her and she offered practical counsel on marriages, children, life.

“What I remember about her is how impassioned she was,” Her Holiness says. “And she was the kind of person who was able to treat everyone equally. What impressed me was how she could empathize with everyone, and read into people. She was a really good listener, and sometimes she would say, ‘You did a very good job.’ She gave very encouraging words. What I also remember is she never looked down on people, and it is these qualities I learned from her.”