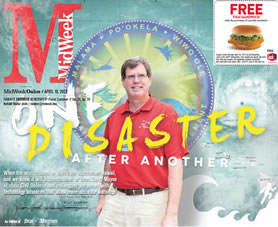

One Disaster After Another

When the next tsunami or hurricane approaches Hawaii, and we know it will happen sooner or later, Doug Mayne of state Civil Defense and colleagues are armed with technology advances that allow more accurate warnings

We live with the daily threat of tsunamis, floods, hurricanes. Thanks to technology advances, Doug Mayne of Civil Defense and others in the disaster biz can provide more timely and more accurate warnings

Doug Mayne’s career is one disaster after another. But we hired him anyway. Actually, it qualifies him for an important job in the state, and when we tell you what he does, you’ll be glad he can dissect a disaster.

Mayne, a retired Army National Guard officer, is vice director of Hawaii State Civil Defense. He is the goto guy at the helm of critical data and procedures for emergency management in our state. His responsibilities cover both response and recovery phases of declared crises to protect lives and property.

Mayne was named to the position in March 2012, succeeding Ed Teixeira, who held the post for 12 years. It is Mayne’s duty to know disasters in detail.

No one likes to think about disasters, whether natural or man-made, but they do happen in our ever-perilous world. This is why it is important for homes, small businesses, and other businesses to ensure that they are protected if there is a storm and are hiring people like Professional arborists Fresno, electricians, and plumbers to sort prevention methods for the storm and help them after the storm too. During April, Tsunami Awareness Month, we get face-to-face with Mayne to review his first year on the job and to look ahead.

Just being in his unique office says everything about Mayne’s world. The Hawaii State Civil Defense headquarters is in Birkhimer Bunker, a military battery built in 1916 at Diamond Head Crater. The windowless enclosure, with 6-foot-thick walls, heavily insulated ceilings and deep dens, is an impenetrable fortress.

But if you have a guest pass, you get a cordial welcome, as we did, and can view historic photos and artifacts on display before entering Mayne’s office. En route, we walk past a communications nerve center known as the State Warning Point with a line of computers and video monitors projecting satellite and radar broadcasts; two conference rooms with teleconferencing capacity; and various office and storage areas.

It’s a tight squeeze in the 5,000-square-foot space when civil defense personnel, government officials, volunteers and media are operating there during an emergency.

But on the day of our visit, it is safe haven for an enlightening exchange about Hawaii’s scope of emergency and disaster management.

Most of us don’t think about Hawaii’s civil defense except when those blaring sirens are tested once a month. Yet we have vivid memories and personal accounts of devastating events, such as the 1946 Hilo tsunami and Hurricane Iniki in 1992, that mark the Islands’ vulnerability.

“Preparing for disasters is a never-ending process,” Mayne says. “We will never be fully prepared. It takes diligent planning and training to address new threats, new technology and turnover.

“Our goal is to have a fully functional, fully integrated emergency-management system so we respond most effectively to disasters,” the 50-year-old administrator says, even while realizing Hawaii’s challenges as an island state.

Fundamentally, disasters are local events, he states. This makes emergency management a community-centric operation, supported by county agencies and grass-roots organizations. It’s not a one-size-fits-all scenario.

“Up until a couple of years ago, disaster response was seen as a government-centric operation,” Mayne cites. “My most important role is to support the county managers to make sure they have whatever they need to protect citizens and communities.”

Just as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has adopted a “whole community” approach of shared responsibility, so has Hawaii moved to defined partnerships with families, businesses, nonprofit and faith-based organizations, as well as community volunteers.

“Disaster preparedness and response involves everybody,” proclaims Mayne, who worked for four years as a FEMA coordinating officer based in Olympia, Wash., where he led responses to seven disasters in six states.

As Hawaii’s vice director of civil defense, he reports to Maj. Gen. Darryll Wong, state Adjutant General and director of state civil defense.

Mayne previously worked with the Hawaii Joint Force HQ staff in 2007 during the annual Makani Pahili disaster-response exercise.

Since moving to Waikiki with wife Cathe and two Boston terriers, Mayne has been entrenched in the dayto-day administration, training and readiness of state civil defense personnel.

After only a few months on the job, Mayne was put through the paces of Hawaii’s Oct. 27 tsunami threat generated from a 7.7 magnitude quake off the west coast of Canada. A statewide alert was issued after buoy readings indicated that Hawaii could be impacted. Although sea level changes and strong currents posed hazards to harbors and marinas, the tsunami warning was fortunately lifted the next day.

“Each incident is a new learning experience,” Mayne recalls. “Typically, we would have had six hours of notice. We ended up with three-and-a-half hours of notice. It’s one of those things where Mother Nature has a lot more out there that we need to know about.”