The Latest Medical Breakthrough At UH

A University of Hawaii surgical instructor and two young engineers join forces to create a medical device that could speed up training and improve medical care — and perhaps save lives.

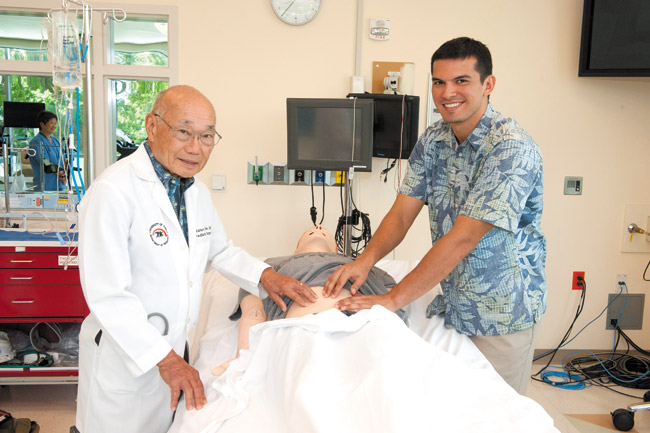

Dr. Walton Shim and engineering graduate student Larry Martin are looking to become major players in the medical technology industry. Along with partner John Salle, a recently graduated engineering student, the trio is developing a medical training device that could save lives, improve patient care and further enhance University of Hawaii’s and John A. Burns School of Medicine’s (JABSOM) reputation as leaders in medical technology.

mw-cover-102214-larrymartin_waltonshim-nwhero

Their device, SmarTummy, is a manikin that can simulate any number of abnormalities in the abdomen. It is the first such device currently under development, and the trio are gearing up to be part of this growing market.

“We are hitting this market at just the right time to take advantage of the product and integrate it into schools,” says

Martin, who first came to our attention a year ago while leading a team of UH engineering students who developed the nano satellite Ho’oponopono 2. The satellite was launched aboard a NASA Minotaur I rocket.

The medical simulation industry is expected to grow from $850 million in 2012 to an estimated $1.9 billion in 2017.

SmarTummy began formulating in the mind of Shim, a medical director at Aloha Care and professor of surgery at JABSOM, in 2006. In his position at the medical school, Shim witnessed firsthand the difficulties of training future doctors and nurses in diagnosing abdominal problems. Patients with appendicitis go to hospitals, not medical schools, for treatment. Therefore, students may not see an actual sick patient until they begin working at a hospital or clinic.

“There is a big need for a manikin that can simulate common medical problems,” says Shim. “This manikin can push ahead training by three years.”

The device works something like this: The manikin’s abdomen is divided into more than 100 regions by two layers of balloons. Through a system of solenoids, air is sent to the individual balloons that mimic the size and texture of the ailment. The top layer represents the size of the faulty organ, and the lower, its density. (One of the first steps in diagnosing an abdominal disorder is to probe the region with one’s fingers to feel for any malformity.) Instructors can dial up specific problems on a computer and rotate between a healthy and unhealthy organ to better help students identify differences. The system also sends feedback to the instructor, who can monitor where and how hard the student is pressing.

How does one come up with such an idea? Ask an organ repairman, apparently.

While working on the pipe organ at St. Clement’s Church, the craftsman explained to Shim how a manifold system distributes air to the organ’s pipes. The amount of air released controls the volume of each note. A concept was born. Shim figured that, if a manikin could be filled with bags and somehow inflated, the bags might re-create the feel of an unhealthy organ.

Bring on the engineers.

In January 2012, Shim presented his idea to a group of students in the university’s biomedical engineering class. The course, developed by Dr. Russell Woo, a surgical faculty member at JABSOM, and Scott Miller, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at UH, brings together doctors and engineering students with the idea of designing new medical products. The pitch struck a chord with Martin.

“He described the problem, and immediately while he was talking I started thinking about how we can do this,” says Martin, who is CEO of SmarTummy. “To me, it was clear a manikin could be discretized and broken up into different regions.”

They got to work.

By the end of the semester, and after a shopping trip to Home Depot to scavenge sprinkler parts, the team had a rough prototype that proved the concept was sound. They presented the prototype to Dr. Thomas Krummel, director of Goodman Simulation Center and chairman of the department of surgery at Stanford University. He was impressed.

Krummel wasn’t the only one.

The trio took their manikin to just about every hospital and medical teaching center on Oahu for technical feedback and to gauge interest.

Opinions were unanimous: They all wanted one.

The team came away with not only advice on how to better their product, but also with letters of support to be later submitted with grant applications. Martin highlights the particular efforts of Dr. Ben Berg, director of SimTiki simulation center at JABSOM, and Dr. Lorrie Wong, director of the UH nursing simulation center, as primary sources of expertise and assistance.

Production of a fully functioning prototype starts and stops with funding. To date, the team has spent $65,000 in development, and Martin estimates the full cost to top $250,000. With the exception of $10,000 provided by Shim, funding has come from contest awards and grants. SmarTummy won $10,000 (plus $7,500 in in-kind services) from the UH Business Plan Competition. The startup placed third in the American Society of Mechanical Engineers Innovation Showcase, winning another $10,000, and $5,000 from National Collegiate Inventors and Innovators Alliance. They are currently searching for investors who share their interest in developing affordable technology that will advance medical care.

The first SmarTummy models will be able to simulate the look, feel and sound of the five most-common abdominal ailments. Later upgrades may diagnose more irregularities, improve performance quality or expand beyond two-legged patients.

SmarTummy 2.0 may find its way into veterinarians’ offices. After all, doggies have tummies, too.