Tiny Technology Finds A Home At UH

When the Minotaur 1 rocket clears the launch pad at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia sometime in the next few days, the members of the UH Small Satellite Research Lab will breathe a collective sigh of relief. That’s not much of a celebration, but after four years of labor, thousands of hours of effort and a failed attempt seven years earlier, a good safe launch is as exciting as it gets.

Once the nanosatellite is deployed and operational, the champagne corks will begin flying and Holmes Hall will start a rockin’.

So don’t bother knocking, they may not hear you.

This is a big deal.

Composed entirely of graduate and undergraduate students at the University of Hawaii, the team will have made history. The Ho’oponopono 2, or H2, satellite will be the first such Hawaii-made object to circle Earth. It also is one of the few student-designed cube satellites to reach space, regardless of home state.

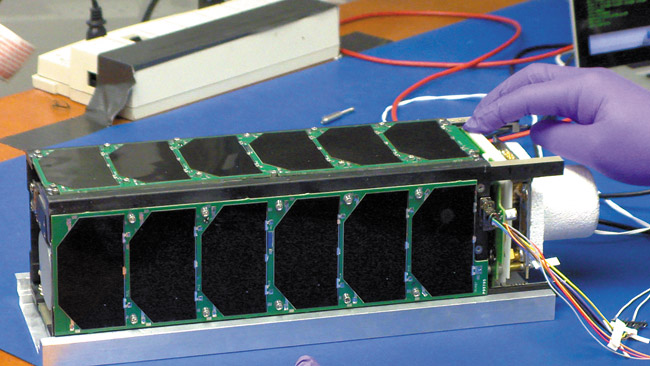

The tiny satellite that is no bigger than a loaf of bread will be used to calibrate Department of Defense radar stations by comparing the satellite’s true position to what the radar station sees. It’s an important job that is critical for the safe operation of commercial and military aircraft, and other objects of interest. The success of H2 is particularly important because the two calibration satellites currently in orbit are well-past their prime. The first, RADCAL, has died, and the second one is on its last leg. RADCAL was launched with a one-year expected lifespan and has lasted 20. H2 has the same initial lifespan goal, and there is good hope it, too, will have a much longer career.

Just as important as the project is to air safety, it also sends the message that local students can compete with the world’s best.

“We are going to be the first small-sat program to get a satellite into space,” says project manager Larry Martin, a Kailua High School graduate. “We will be representing the entire state, and I think that says a lot about our students and the program.”

Once the satellite is up and running, lab members will monitor its activity through a shared antenna agreement with Sacred Hearts Academy. UH gets to use the school’s antenna, and Sacred Hearts students receive unprecedented access to new technology. It’s a win-win for both schools.

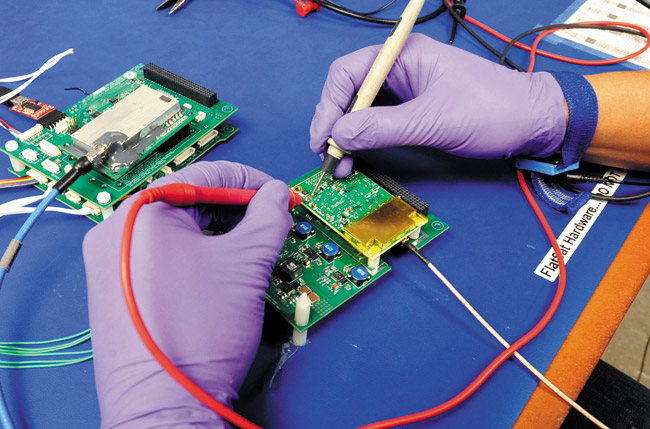

The small-satellite lab was created in 2001 by professor Wayne Shiroma to provide engineering students with hands-on experience to supplement their theoretical studies. It’s worked wonderfully and has kept the university on the cutting edge of micro-and nanotechnologies.

“Many universities don’t actually climb up that tree,” says graduate student Windell Jones, a Waipahu High School grad and the project’s attitude control subsystem and structural subsystem engineer. “We are one of the few universities that are actually pushing the envelope.”

UH produced its first satellite in 2006, but it was destroyed when the rocket crashed on ascent.

The team got its next shot at the big time in 2009, when the school was chosen to take part in the Air Force’s University Nanosatellite Program. This alone was a major accomplishment, as only 12 universities were chosen to compete.

The select few were given $110,000 to create a plan to design and build a satellite. A panel examined the submissions, with the winner getting two years of development time, another $110,000 and a free ride aboard the rocket. UH took third behind Cornell and Michigan Tech universities, and was named most improved. On the heels of this success, the team applied to NASA’s Educational Launch of Nanosatellites Program, which accepted its plan and gave the team a coveted rocket space. The Air Force then kicked in $110,000 to complete the project. It was the second time UH had been selected to compete.

Acceptance confirmed, they designed a beneficial advancement in the field of small-satellite technology.

“Our project demonstrates the ability to down-size and build something that is smaller, cheaper and do it in a much more rapid fashion that can have the same capabilities as their larger counterparts,” says Martin.

What began on a shoestring budget not so many years ago has paid off nicely for both the university and its students. The program has produced employment opportunities and internships at several high-profile engineering companies for its members. Martin even got to work on the B-2 Bomber.

“It was the coolest thing I have done by far,” says the smiling engineer, who last year started Smart Tummy, a company that makes abdominal simulators that can replicate tumors and ailments, and will be used to train nurses and EMS students.

As part of the Air Force’s competition, Martin was named the most outstanding electrical engineering student in the nation, winning the 2011-12 Alton B. Zerby and Carl T. Koerner Outstanding Electrical and Computer Engineering Student Award.

It’s just another feather in the cap for the program Shiroma started.

“Traditional engineering schools try to teach you how to be an engineer, they give you lessons on the blackboard, but they (the program members) are actually doing it. They are working with customers, with the government. This is a very rare opportunity we are giving students, so when they get out there, they are not just hitting the ground running, they are sprinting.”

The success of the small-satellite lab has birthed two new programs that Shiroma believes will further advance the university’s reputation as a leader in advanced engineering.

One is a drone program that will provide low-cost wireless communication in disasters areas. The other is a marine robotics program that will tap into the already successful high school STEM programs and robotics teams. It will be years before these new programs start developing their own versions of Ho’oponopono 2.

But think about it: “Hawaii, the home of sun, surf, sand and high technology.”

It has a nice ring.