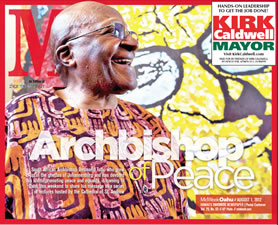

Archbishop of Peace

South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who grew up in the ghettos of Johannesburg and has devoted his life to promoting peace and equality, is coming to Oahu this weekend to share his message in a series of lectures hosted by the Cathedral of St. Andrew

Nobel Peace Prize laureate Desmond Tutu, the Anglican Church Archbishop Emeritus of South Africa, visits Oahu this week for a series of lectures and special appearances

While Archbishop Desmond Tutu is best known for helping the blacks of his native South Africa unshoulder the yoke of white oppression enforced through their draconian apartheid laws, it is his keen understanding of the many shades of gray that make up all men that has allowed his message to succeed in the world.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Tutu, who will visit the Islands next week for a series of lectures, grew up in the ghettos of Johannesburg, and from a young age recognized that as George Orwell once wrote, “all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

“I would see black kids scavenging in the dustbins of the schools where they picked out perfectly OK apples and fruit,” said Tutu in an interview with the Academy of Achievement, a museum of living history in Washington, D.C. “White kids were being provided with school feeding, government school feeding, but most of the time they didn’t eat it. They preferred what their mommies gave them, and so they would dump the whole fruit into the dustbin, and these kids coming from a township who needed free meals didn’t get them. It was things like that which registered without your being aware that they were registering and you’re saying there are these extraordinary inconsistencies in our lives.”

This impression of inequality could have caused a young Tutu to take a very dark view of the white minority that ruled his land, but he was a remarkably prescient kid despite being a self-proclaimed “OK student,” and noticed that not everything is as it seems, that bad governance does not necessarily make bad people.

“I would go to town in part to go and buy newspapers for my father and, before taking them home, I would spread them on the sidewalk, and I would kneel to read,” said Tutu. “Now this is a racist town, yet I can’t ever recall any day when what should have happened, in fact, did happen, which is that a white person would walk across the face of the newspaper.

“I still am puzzled that they used to walk around this newspaper with this black kid kneeling down there reading when you would have expected that they would have made my life somewhat uncomfortable. I mean, I cannot understand that particular inconsistency. It is, therefore, one of my memories that why in the name of everything that is good didn’t those whites actually just be nasty, and they weren’t.”

These two seemingly conflicting memories of his youth helped form the man who originally was destined to be a healer of bodies but instead became a mender of souls. Medical school was too expensive for the son of a teacher and a domestic worker, so he followed his father’s route, trained to be an educator and returned to his alma mater.

But Tutu was not to be long in the classroom. Deplorable conditions, overcrowded facilities and the initiation of the Bantu curriculum made him realize he could not stay on and assist the apartheid government in the corruption of young minds.

“But then I decided, no, I would not participate any longer as a collaborator, when the government decided that they were going to have something called Bantu education, an education specifically designed for blacks, and they made no bones about the fact that it was designed as education for perpetual serfdom.

“Dr. Favolt said, ‘Why do you have to teach blacks mathematics? What are they going to do with mathematics? You must teach them enough English and Afrikaans, the other white language as it were, for them to be able to understand instructions given to them by their white employers.’ He said that. I mean, unabashedly that was the purpose for him of education. So I said, ‘No, I’m sorry. I can’t collaborate with such a travesty,’ but I didn’t have too many alternatives, too many options to choose from.”

The only sensible option open to him was in the priesthood, and it proved to be the perfect one to help foster the empathy for his fellow man that had sprouted in him in his youth. Despite leaving the education field, he continued to beat the drum for it, saying that if the next generations of blacks were to lead their nation, they needed to be educated to do the task.

His ability to separate the man from his sins is best embodied in his thanking of the infamous Minister of Police Louis le Grange for allowing prisoners to do post-matriculation studies while imprisoned. It takes a man of tremendous soul to extend that olive branch to the man who later masterminded the bombing of the African National Congress Building in London, but such was Tutu’s devotion to educating his people.

He rose through the church, some of his time spent in England but always returning to his homeland, where the white leaders could pretend to ignore his message but could no longer fail to hear it. He warned Prime Minister John Vorster in 1976 of the impending danger if they did not loosen their grip on the black community. Vorster ignored his plea and the bloody uprising of the Soweto students soon followed.

“I spoke to some of them (the students) and said, ‘You know, are you aware that if you continue to behave in this way, they will turn their dogs on you, they will whip you, they may detain you without trial, they will torture you in their jails, and they may even kill you?'” said Tutu. “It was almost like bravado on the part of these kids because almost all of them said, ‘so what? It doesn’t matter if that happens to me, as long as it contributes to our struggle for freedom,’ and I think 1994, when Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as the first democratically elected president, it vindicated them. It was the vindication of those 1977 remarkable kids.”

In 1978 he became the general secretary of the South Africa Council of Churches. This finally gave Tutu the pulpit he needed to be heard worldwide, where he not only beat the drum against the atrocities of his own country, but once again demonstrated his colossal empathy by appealing to Israeli Prime Minister

Begin to stop bombing Beirut and for Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat to exercise a “greater realism regarding Israel’s existence.”

His evenhandedness in all affairs and steadfastness to the cause of his black countrymen netted him the Nobel Prize for Peace, ironically in 1984, the year made famous by an Orwell novel whose government bore such an eerie resemblance to that of South Africa’s at the time.

His work for peace has not slackened through the years, and even now at 80 he continues to do work as the chairman of the Elders, a private initiative that mobilizes world leaders outside of the conventional diplomatic process. Here he works with the likes of Jimmy Carter, Kofi Annan and Nelson Mandela on problems such as those in Darfur and the Gaza Strip.

Tutu will be appearing five times during his three-day visit. If you would like to see the archbishop in person, here are the opportunities available:

>> Aug. 3, 6 p.m. – An Evening With Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the Cathedral of Saint Andrew. Tutu will engage in a conversation with Leslie Wilcox, president and CEO of PBS Hawaii, in the historic cathedral. Prior to the conversation, guests will enjoy a reception catered by the Halekulani. Tickets cost $500 per person for reserved seating, and $1,000 per person for the Archbishop’s Circle, which includes premium reserved seating near the conversation stage, a special reception and photo with Archbishop Tutu.

>> Aug. 4, 10 a.m. – The Peggy Kai Memorial Lecture at Tenney Theater, at the Cathedral of Saint Andrew. Free to the public, but seating is limited and reservations are required. Two tickets will be allowed per person.

>> Aug. 4, 5 p.m. – Bishop’s Luau at the Bishop Museum. The Right Rev. Robert L. Fitzpatrick, Bishop of Hawaii, will host an evening with Tutu featuring Hawaiian food, traditions and entertainment. Tickets cost $75 per person.

>> Aug. 5, 9:30 a.m. – Choral Eucharist at the Cathedral of Saint Andrew. Tutu will be the preacher for the Sunday Holy Communion service. The public is invited; there is no admission charge.

>> Aug. 5, 5:30 p.m. – Interfaith Prayer Service at the Cathedral of Saint Andrew. Archbishop Tutu will join Hawaii faith leaders for an interfaith prayer service. He will participate in the service, but is not scheduled to speak. The public is invited; there is no admission charge.

For more information and to buy tickets or make reservations for any of the events, go to tutuatthecathedralofstandrew.org, or call 524-2822, ext. 577.