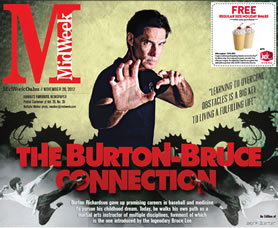

The Burton-Bruce Connection

“Do not pray for an easy life. Pray for the strength to endure a difficult one.” – Bruce Lee

To family and friends, Richardson had everything a young man could ever want: a stable home life, a promising sports career and a clear pathway to becoming a surgeon.

So it was utterly shocking for them when shortly before his senior year at USC, the biology major’s heart, which had never before failed him, simply quit. Essentially, he had come to the conclusion that college baseball and academia were no longer the forces that made his world go round. And so he walked away from it all.

“I was physically sick, tired and burned out mentally,” Richardson admits. “Growing up, my father had high standards and wanted me to achieve, and although I am thankful for him pushing me, I was achieving things that really weren’t for me.

“I didn’t play my fourth year of baseball. I didn’t even show up for medical school.”

When he finally stopped walking, he found himself a couple of miles from downtown Los Angeles, in a seedy area along West Washington Boulevard. For the next five years, Richardson lived in a trailer that belonged to the Washington Dog and Cat Hospital, dwelling in what he would refer to as “abject poverty” and surviving on a diet that consisted mostly of ramen, or shoyu and rice with vegetables.

Good meals were scarce, and an environment fraught with peril was always present. Located just across the street was a drug house that addicts visited at all hours of the day and night. Even worse, gunshot sounds were as frequent as police sirens, ringing out from seemingly every dimly lit corner on the block.

“There were a lot of gang wars going on at that time in L.A.,” Richardson recalls. “Once, I walked out of an alley near the hospital and a couple of guys suddenly appeared and put a shotgun to my neck. Fortunately, I was able to stay calm and one of them looked at me and said, ‘Wrong guy.'”

For most, remaining in such hellish conditions would indicate a wrong choice in life – but not Richardson. While it certainly wasn’t the day-to-day existence he hoped for, it was the first time he actually felt content and in control of his destiny.

Or, as he says, “I may have been living in a trailer and in a very dangerous area, but at least I was doing what I wanted. I was finally walking my own path.”

“To hell with circumstances! I create opportunities.” – Bruce Lee

Richardson’s immediate surroundings may have been littered with many of society’s ills, but the greater area of Southern California was still ripe with possibilities. Located in Marina Del Ray, for example, was the Inosanto Academy operated by Dan Inosanto, a student and close friend of Lee’s who became the foremost authority on jeet kune do following the international film star’s sudden death in 1973.

Richardson first became aware of the martial arts world while in elementary school, although his father forbade him from taking self-defense classes because Burton Sr. feared it would interfere with baseball. But with the sport safely out of the picture after his departure from USC, Richardson felt free to finally pursue a childhood dream. Almost immediately, he signed up for the academy’s Saturday classes in jeet kune do and Jun Fan Gung Fu (literally, “Bruce Lee’s Kung Fu”). Later on, he followed Inosanto to his I.M.B. Academy in Carson City, where he would take courses throughout the week in Thai boxing, kickboxing, kali and other forms of Filipino martial arts.

“Wherever Sifu Dan went around town to teach a class, I was there. And whatever money I made working at a delivery service, I’d save some for food and the rest went to pay for training at his classes,” says Richardson, whose introduction to the martial arts world was anything but smooth back then, in large part because he was overweight and possessed rather stiff hips.

But just as he did in baseball, he trained relentlessly at the academies. And in between lessons and late at nights, he would pore through countless self-help books, beginning with Lee’s Tao of Jeet Kune Do, and find motivation to do as the master counseled, which was to go beyond one’s plateaus, or self-imposed limits.

“Everyone has the ability to change and improve,” says Richardson. “We don’t have to remain victims of circumstance; we don’t have to be a part of the ‘woe is me’ crowd and continue to feel sorry for ourselves. All of us have the ability to respond and do something positive with our lives.”

Armed with this knowledge, Richardson began noticing that more opportunities for personal growth were materializing. After becoming an apprentice instructor under Inosanto, for example, Richardson helped form a group known as the Dog Brothers, a collection of a dozen or so avid martial artists who, in adopting Lee’s famous “boards don’t hit back” statement, chose to see what would happen in a real fight, where live opponents did hit back with weapons such as heavy rattan sticks, and where there were no rules other than “to not kill each other.” Soon, the Battlefield Kali family was organized and the program, featuring sparring-based weaponry training, continues to this day.

“Our feeling was that you had to test yourself against someone else to see if your fighting skills really worked,” explains Richardson, who was tagged with the nickname “Lucky Dog” at the time because of all the good fortune that was suddenly coming his way. “We can theorize all we want to, but in the end, if the skill doesn’t work, why use it?”

“Real living is living for others.” – Bruce Lee

If there is anything “lucky” about Richardson’s life, it’s that he has been in position to learn from and train with many of the world’s finest martial artists. And if there is anything worthy and notable about his character, it’s that he has made the most of his chances – whereas others might have squandered these same “lucky” opportunities.

Inosanto remains his principal living influence, but there have been others who were instrumental in training Richardson: two of Lee’s other pupils, Richard Bustillo and Larry Hartsell, both of whom were sifus in jeet kune do and Filipino martial arts; Chai Sirisute in Thai boxing; Eric Knaus, a founding member and primary driving force behind the weapons-based group Dog Brothers; Antonio Illustrisimo, the legendary grand master of kali; and Herman Suwanda and Paul De Thouars in the Indonesian fighting form penchak silat, just to name a few. Even Hawaii’s Egan Inoue has played a significant role in teaching Richardson the Brazilian jiu-jitsu fighting system.

With so much of others’ time given to his development, Richardson feels obligated to repay the debt.

“You know, I chose not to become a doctor many years ago, but I think I’m in a unique situation where I can still help people to heal,” says Richardson, who often travels the world to give seminars or learn often inaccessible fighting systems, such as when he traveled to South Africa to study Zulu stick fighting. “See, a lot of people talk about being happy, but I’d rather spend my time learning how to be fulfilled, and then teach others how to be fulfilled, too.”

One of those students who needed to be fulfilled happened to be the son of a rather famous martial artist:

“Sifu Dan came up to me one day back in the early ’90s and said there was a young guy he wanted me to take under my wings and work with. Naturally, as one of his instructors, I said OK,” Richardson recalls. “Well, in walks Brandon Lee.”

Over the next 18 months, Richardson challenged the up-and-coming actor to reach his potential, preparing Lee’s son for a string of action-packed films that would define a career and life cut tragically short at just age 28.

“Brandon was definitely not a natural. He wasn’t terribly coordinated and he was a bit stiff. But he was quick, and he had his father’s tenacity in him. And the thing about Brandon was he trained so, so hard,” Richardson says. “He really developed into quite a martial artist.”

Thanks, in part, to Richardson’s role as a teacher.

“Burton’s dedication to the arts, combined with his open mind, natural attributes and drive for personal growth and knowledge, has never wavered,” says Inosanto. “His skill and ability to teach and coach his students and ‘fighters’ make him a remarkable martial artist.”